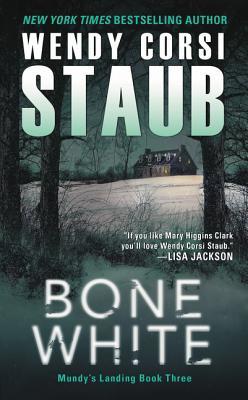

New York Times Bestselling Author Wendy Corsi Staub revisits Mundy’s Landing—a small town with a blood-soaked past.

The town of Mundy’s Landing was founded on a horrifying secret, but stark white bones of the dead never lie…

“We shall never tell.” Spurred by the cryptic phrase in a centuries-old letter, Emerson Mundy travels to her ancestral hometown to trace her past. In Mundy’s Landing, she connects with long lost relatives—and a closet full of skeletons going back centuries.

In the year since former NYPD Detective Sullivan Leary solved the historic Sleeping Beauty Murders, she—like the village itself—has made a fresh start. But someone has unearthed blood-drenched secrets in a disembodied skull, and is hacking away at the Mundy family tree, branch by branch…

My review :- Addictive,thrilling and unique. The plot was well developed, captivating and well structured with strong and intriguing characters, bone chilling mystery and a prose that was an adventure to read in itself. A solid 4.3 stars book that I deem perfect for every thriller or mystery fan.

Book Details:

Genre: Thriller/Suspense

Published by: William Morrow Mass Market

Publication Date: March 28, 2017

Number of Pages: 384

ISBN: 0062349775 (ISBN13: 9780062349774)

Series: Mundy’s Landing #3 (Stand Alone)

Purchase Links: Amazon | Barnes & Noble

| Barnes & Noble  | Goodreads

| Goodreads

Published by: William Morrow Mass Market

Publication Date: March 28, 2017

Number of Pages: 384

ISBN: 0062349775 (ISBN13: 9780062349774)

Series: Mundy’s Landing #3 (Stand Alone)

Purchase Links: Amazon

| Barnes & Noble

| Barnes & Noble  | Goodreads

| Goodreads

Read an excerpt:

Chapter 1

July 20, 2016

Los Angeles, CA

We shall never tell.

Strange, the thoughts that go through your head when you’re standing at an open grave.

Not that Emerson Mundy knew anything about open graves before today. Her father’s funeral is the first she’s ever attended, and she’s the sole mourner.

Ah, at last, a perk to living a life without many—any—loved ones; you don’t spend much time grieving, unless you count the pervasive ache for the things you never had.

The minister, who came with the cemetery package and never even met Jerry Mundy, is rambling on about souls and salvation. Emerson hears only We shall never tell—the closing line in an old letter she found yesterday in the crawl space of her childhood home. It had been written in 1676 by a young woman named Priscilla Mundy, addressed to her brother, Jeremiah.

The Mundys were among the seventeenth-century English colonists who settled on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, about a hundred miles north of New York City. Their first winter was so harsh the river froze, stranding their supply ship and additional colonists in the New York harbor. When the ship arrived after the thaw, all but five settlers had starved to death.

Jeremiah; Priscilla; their sister, Charity; and their parents had eaten human flesh to stay alive. James and Elizabeth Mundy swore they’d only cannibalized those who’d already died, but the God-fearing, well-fed newcomers couldn’t fathom such wretched butchery. A Puritan justice committee tortured the couple until they confessed to murder, then swiftly tried, convicted, and hanged them.

“Do you think we’re related?” Emerson asked her father after learning about the Mundys back in elementary school.

“Nope.” Curt answers were typical when she brought up anything Jerry Mundy didn’t want to discuss. The past was high on the list.

“That’s it? Just nope?”

“What else do you want me to say?”

“How about yes?”

“That wouldn’t be the truth,” he said with a shrug.

“Sometimes the truth isn’t very interesting.”

She had no one else to ask about her family history. Dad was an only child, and his parents, Donald and Inez Mundy, had passed away before she was born. Their headstone is adjacent to the gaping rectangle about to swallow her father’s casket. Staring that the inscription, she notices her grandfather’s unusual middle initial.

Donald X. Mundy, Born 1900, Died 1972.

X marks the spot.

Thanks to her passion for history and Robert Louis Stevenson, Emerson’s bookworm childhood included a phase when she searched obsessively for buried treasure. Money was short in their household after two heart attacks left Jerry Mundy on permanent disability.

X marks the spot…

No gold doubloon treasure chest buried here. Just dusty old bones of people she never knew.

And now, her father.

The service concludes with a prayer as the coffin is lowered into the ground. The minister clasps her hand and tells her how sorry he is for her loss, then leaves her to sit on a bench and stare at the hillside as the undertakers finish the job.

The sun is beginning to burn through the thick marine layer that swaddles most June and July mornings. Having grown up in Southern California, she knows the sky will be bright blue by mid-afternoon. Tomorrow will be more of the same. By then, she’ll be on her way back up the coast, back to her life in Oakland, where the fog rolls in and stays for days, weeks at a time. Funny, but there she welcomes the gray, a soothing shield from real world glare and sharp edges.

Here the seasonal gloom has felt oppressive and depressing.

Emerson watches the undertakers finish the job and load their equipment into a van. After they drive off, she makes her way between neat rows of tombstones to inspect the raked dirt rectangle.

When something is over, you move on, her father told her when she left home nearly two decades ago. She attended Cal State Fullerton with scholarships and maximum financial aid, got her master’s at Berkeley, and landed a teaching job in the Bay Area.

But she didn’t necessarily move on.

Every holiday, many weekends, and for two whole months every summer, she makes the six-hour drive down to stay with her father. She cooks and cleans for him, and at night they sit together and watch Wheel of Fortune reruns.

It used to be because she craved a connection to the only family she had in the world. Lately, though, it was as much because Jerry Mundy needed her.

He pretended that he didn’t, that he was taking care of himself and the house, too proud to admit he was failing. He was a shadow of his former self when he died at seventy-six, leaving Emerson alone in the world.

Throughout her motherless childhood, Emerson was obsessed with novels about orphans. Treasure Island shared coveted space on her bookshelf with Anne of Green Gables, The Secret Garden, The Witch of Blackbird Pond…

She always wondered what would happen to her if her father died. Would she wind up in an orphanage? Would a kindly stranger take her in? Would she live on the streets?

Now that it’s happened he’s down there, in the dirt … moving on?

She’ll never again hear his voice. She’ll never see the face so like her own that she can’t imagine she inherited any physical characteristics from her mother, Didi—though she can’t be certain.

Years ago, she asked her father for a picture—preferably one that showed her mother holding her as a baby, or of her parents together. Maybe she wanted evidence that she and her father had been loved; that the woman who’d abandoned them had once been normal—a proud new mother, a happy bride.

Or was it the opposite? Was she hoping to glimpse a hint that Didi Mundy was never normal? Did she expect to confirm that people—normal people—don’t just wake up one morning and choose to walk out on a husband and child? That there was always something off about her mother: a telltale gleam in the eye, or a faraway expression—some warning sign her father had overlooked. A sign Emerson herself would be able to recognize, should she ever be tempted to marry.

But there were no images of Didi that she could slip into a frame, or deface with angry black ink, or simply commit to memory.

Exhibit A: Untrustworthy.

Sure, there had been plenty of photos, her father admitted unapologetically. He’d gotten rid of everything.

There were plenty of pictures of her and Dad, though.

Exhibit B: Trustworthy.

Dad holding her hand on her first day of kindergarten, Dad leading her in an awkward waltz at a father-daughter middle school dance, Dad posing with her at high school graduation.

“Two peas in a pod,” he liked to say. “If I weren’t me, I’d think you were.”

She has his thick, wavy hair, the same dimple on her right cheek, same angular nose and bristly slashes of brow. Even her wide-set, prominent, upturned eyes are the same as his, with one notable exception.

Jerry Mundy’s eyes were a piercing blue.

Only one of Emerson’s is that shade; the other, a chalky gray.

***

Excerpt from Bone White by Wendy Corsi Staub. Copyright © 2017 by Wendy Corsi Staub. Reproduced with permission from William Morrow Mass Market. All rights reserved.

Los Angeles, CA

We shall never tell.

Strange, the thoughts that go through your head when you’re standing at an open grave.

Not that Emerson Mundy knew anything about open graves before today. Her father’s funeral is the first she’s ever attended, and she’s the sole mourner.

Ah, at last, a perk to living a life without many—any—loved ones; you don’t spend much time grieving, unless you count the pervasive ache for the things you never had.

The minister, who came with the cemetery package and never even met Jerry Mundy, is rambling on about souls and salvation. Emerson hears only We shall never tell—the closing line in an old letter she found yesterday in the crawl space of her childhood home. It had been written in 1676 by a young woman named Priscilla Mundy, addressed to her brother, Jeremiah.

The Mundys were among the seventeenth-century English colonists who settled on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, about a hundred miles north of New York City. Their first winter was so harsh the river froze, stranding their supply ship and additional colonists in the New York harbor. When the ship arrived after the thaw, all but five settlers had starved to death.

Jeremiah; Priscilla; their sister, Charity; and their parents had eaten human flesh to stay alive. James and Elizabeth Mundy swore they’d only cannibalized those who’d already died, but the God-fearing, well-fed newcomers couldn’t fathom such wretched butchery. A Puritan justice committee tortured the couple until they confessed to murder, then swiftly tried, convicted, and hanged them.

“Do you think we’re related?” Emerson asked her father after learning about the Mundys back in elementary school.

“Nope.” Curt answers were typical when she brought up anything Jerry Mundy didn’t want to discuss. The past was high on the list.

“That’s it? Just nope?”

“What else do you want me to say?”

“How about yes?”

“That wouldn’t be the truth,” he said with a shrug.

“Sometimes the truth isn’t very interesting.”

She had no one else to ask about her family history. Dad was an only child, and his parents, Donald and Inez Mundy, had passed away before she was born. Their headstone is adjacent to the gaping rectangle about to swallow her father’s casket. Staring that the inscription, she notices her grandfather’s unusual middle initial.

Donald X. Mundy, Born 1900, Died 1972.

X marks the spot.

Thanks to her passion for history and Robert Louis Stevenson, Emerson’s bookworm childhood included a phase when she searched obsessively for buried treasure. Money was short in their household after two heart attacks left Jerry Mundy on permanent disability.

X marks the spot…

No gold doubloon treasure chest buried here. Just dusty old bones of people she never knew.

And now, her father.

The service concludes with a prayer as the coffin is lowered into the ground. The minister clasps her hand and tells her how sorry he is for her loss, then leaves her to sit on a bench and stare at the hillside as the undertakers finish the job.

The sun is beginning to burn through the thick marine layer that swaddles most June and July mornings. Having grown up in Southern California, she knows the sky will be bright blue by mid-afternoon. Tomorrow will be more of the same. By then, she’ll be on her way back up the coast, back to her life in Oakland, where the fog rolls in and stays for days, weeks at a time. Funny, but there she welcomes the gray, a soothing shield from real world glare and sharp edges.

Here the seasonal gloom has felt oppressive and depressing.

Emerson watches the undertakers finish the job and load their equipment into a van. After they drive off, she makes her way between neat rows of tombstones to inspect the raked dirt rectangle.

When something is over, you move on, her father told her when she left home nearly two decades ago. She attended Cal State Fullerton with scholarships and maximum financial aid, got her master’s at Berkeley, and landed a teaching job in the Bay Area.

But she didn’t necessarily move on.

Every holiday, many weekends, and for two whole months every summer, she makes the six-hour drive down to stay with her father. She cooks and cleans for him, and at night they sit together and watch Wheel of Fortune reruns.

It used to be because she craved a connection to the only family she had in the world. Lately, though, it was as much because Jerry Mundy needed her.

He pretended that he didn’t, that he was taking care of himself and the house, too proud to admit he was failing. He was a shadow of his former self when he died at seventy-six, leaving Emerson alone in the world.

Throughout her motherless childhood, Emerson was obsessed with novels about orphans. Treasure Island shared coveted space on her bookshelf with Anne of Green Gables, The Secret Garden, The Witch of Blackbird Pond…

She always wondered what would happen to her if her father died. Would she wind up in an orphanage? Would a kindly stranger take her in? Would she live on the streets?

Now that it’s happened he’s down there, in the dirt … moving on?

She’ll never again hear his voice. She’ll never see the face so like her own that she can’t imagine she inherited any physical characteristics from her mother, Didi—though she can’t be certain.

Years ago, she asked her father for a picture—preferably one that showed her mother holding her as a baby, or of her parents together. Maybe she wanted evidence that she and her father had been loved; that the woman who’d abandoned them had once been normal—a proud new mother, a happy bride.

Or was it the opposite? Was she hoping to glimpse a hint that Didi Mundy was never normal? Did she expect to confirm that people—normal people—don’t just wake up one morning and choose to walk out on a husband and child? That there was always something off about her mother: a telltale gleam in the eye, or a faraway expression—some warning sign her father had overlooked. A sign Emerson herself would be able to recognize, should she ever be tempted to marry.

But there were no images of Didi that she could slip into a frame, or deface with angry black ink, or simply commit to memory.

Exhibit A: Untrustworthy.

Sure, there had been plenty of photos, her father admitted unapologetically. He’d gotten rid of everything.

There were plenty of pictures of her and Dad, though.

Exhibit B: Trustworthy.

Dad holding her hand on her first day of kindergarten, Dad leading her in an awkward waltz at a father-daughter middle school dance, Dad posing with her at high school graduation.

“Two peas in a pod,” he liked to say. “If I weren’t me, I’d think you were.”

She has his thick, wavy hair, the same dimple on her right cheek, same angular nose and bristly slashes of brow. Even her wide-set, prominent, upturned eyes are the same as his, with one notable exception.

Jerry Mundy’s eyes were a piercing blue.

Only one of Emerson’s is that shade; the other, a chalky gray.

***

Excerpt from Bone White by Wendy Corsi Staub. Copyright © 2017 by Wendy Corsi Staub. Reproduced with permission from William Morrow Mass Market. All rights reserved.

I had trouble putting this book down!

ReplyDelete